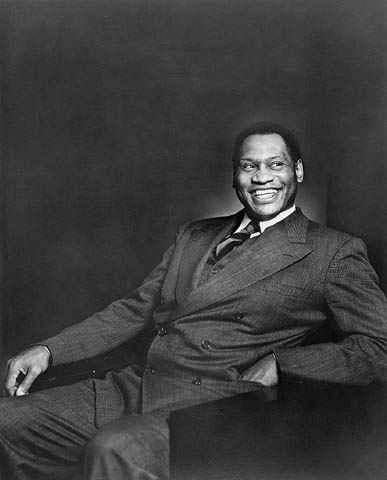

Paul Leroy Robeson was a Renaissance man who spent most of his life fighting injustice, for which he was roundly persecuted. He was an actor, orator, athlete, lawyer, singer, author, scholar, activist and linguist. Most of all, the “tallest man in the forest” – he stood 6-foot-3 – was an authentic American Hero.

He was born April 9, 1898, in Princeton, NJ, the son of a former slave who became an educated minister and a Quaker mother – the Rev. William Drew Robeson and Maria Louisa Bustill. The Bustills were a prominent Philadelphia family with a storied history: Maria’s great-grandfather, a baker, supplied bread to Washington’s army during the Revolutionary War and founded a mutual-aid society for blacks.

In 1933, a magazine wrote asking Robeson for the correct pronunciation of his last name:

“The name is: Robeson: Robe as in the ordinary word, robe, meaning dress, and son pronounced like the word son, meaning a male child,” he explained. “The name is pronounced in two syllables only: Robe-son.”

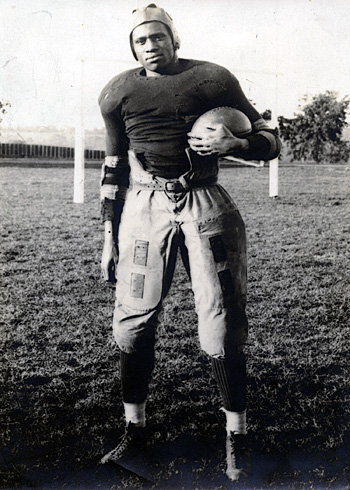

Robeson attended Rutgers College on an academic scholarship, played five sports and won recognition as an All-American football player, was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, and graduated valedictorian of his class at a time when most African Americans were denied entrance to white colleges. Even so, he was tormented on the gridiron; one player crushed his cleats into Robeson’s hand, tearing loose some fingernails.

Robeson persevered, and after Rutgers he attend law school at Columbia University in New York, and got a job at a local law firm after graduation. He left after the firm’s stenographer refused to take dictation from him because he was black. He found his way back into the theater, where he had appeared in the all-black “Shuffle Along” and other musicals while in law school, and never looked back.

He met his future wife Eslanda Cardozo Goode, also from a prominent family, while in law school in the 1920s. They had a son whom they named Paul Jr. Essie, as she was called, became a noted anthropologist, author and civil rights activist alongside her husband.

Robeson’s career spanned nearly 50 years, starting in 1915 at Rutgers. He went on to become a prolific entertainer both in the United States and abroad, playing title roles in “Othello,” “Showboat,” “The Emperor Jones” and other Broadway plays. He recorded albums and filled concert halls.

Early on, Robeson was one of the best-paid performers in the country. He brought African American spirituals to people who did not see it a serious musical form. He held several concerts and shows in Philadelphia, where his sister Marian Forsythe lived.

His accompanist of 40 years was Lawrence Benjamin Brown, a composer of spirituals. Brown accompanied Robeson on tours and recordings.

Robeson came to Philadelphia for many performances. In the winter of 1924-25, he appeared in “The Emperor Jones” at the Walnut Street Theater. In the 1940s, he sang spirituals at the Robin Hood Dell East outdoor arena, with a turnout at one concert of more than 7,500 people. He also sang with the Philadelphia Orchestra on several occasions. Robeson performed “John Henry” at the Erlanger Theater in 1939. He sang and spoke at a Progressive Party rally in 1948 in Shibe Park in support of presidential candidate Henry Wallace.

His mindset and popularity changed after he first went to Russia in 1934 and found that he was treated better there than in the United States. He spoke in support of workers and common people both abroad and in this country, and marched against discrimination.

“Here, I am not a Negro but a human being for the first time in my life. … I walk in full human dignity,” he told reporters about his experience in Russia.

His actions made him a pariah in the eyes of many. J. Edgar Hoover and his FBI put Robeson and Eslanda under surveillance in 1941 (it lasted until Robeson died in Philadelphia in 1976), the House Un-American Activities Committee called him to testify as a perceived Communist in 1956, and the State Department revoked his passport in 1950, preventing him from traveling abroad for concerts that had helped provide his salary.

Many of Robeson’s concerts were canceled. Record companies were no longer interested in recording his songs. His income dropped from six figures to four. He suffered both financially and health-wise.

During his appearance before the House committee (Eslanda was also called and her passport was also revoked), he refused to answer a question about whether or not he was a Communist.

Instead, he said, “I am not being tried for whether I am a Communist, I am being tried for fighting for the rights of my people who are still second-class citizens in this United States of America. …

“You want to shut up every Negro who has the courage to stand up and fight for the rights of his people, for the rights of workers and I have been on many a picket line for the steelworkers too. And that is why I am here today.”

A U.S. Supreme Court ruling in a similar case in 1958 reinstated the couple’s passports. Robeson eventually regained some of his stature, but he and his accomplishments are still not fully recognized or acknowledged today.

In 1966, Robeson came to Philadelphia, and remained here under the protective eye of his sister Marian until his death in 1976.