During the last years of a celebrated – and needlessly torturous – life, Paul Robeson came to live under the watchful eye of his sister Marian R. Forsythe in this three-story home at 4951 Walnut Street.

Forsythe and her husband Dr. James Forsythe bought the house in the late 1950s and moved in with their daughter, Paulina. After Robeson’s wife Eslanda died in 1965, he visited his sister (her husband died in 1959) the following summer before returning to New York to live with his son Paul Jr. Forsythe was a retired Philadelphia schoolteacher and at 72 was four years older than her brother.

He had felt so comfortable in her home that instead of staying in New York, he returned to Philadelphia in the fall of 1966 to live with Marian.

“Paul had missed her and the warm happy surroundings of her home,” Charlotte Turner Bell wrote in her book “Paul Robeson’s Last Days in Philadelphia.”

“The thought of Sis always brings an inner smile,” Robeson wrote in his 1958 book “Here I Stand.” “… As a girl she brought to our household the blessing of laughter, so filled is she with warm good humor.”

Marian took great care of Robeson. She celebrated his birthday every year with a cake. In Philadelphia, she sat with him on the porch as Robeson waved hello to neighbors, many of whom likely did not know who he was or his significance. Soon after he arrived, Marian asked Bell to drop by a few times a week to accompany Robeson on piano.

With Bell at piano, he sang his favorite songs, including “Ol’ Man River,” “We are Climbing Jacob’s Ladder” and “Water Boy.”

He recited “The Creation” by James Weldon Johnson as she softly played “This Little Light of Mine,” him finishing his rendition by singing the song, Bell recalled in her book. He recited Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address” as she played the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” again singing the song himself at the end of the recitation.

“He would sit with his eyes closed while singing and a broad smile on his face,” Bell said in her book. “Most of the time he sang sitting by the piano.”

Bell was not the only one who played for Robeson. Elizabeth Arnold Michael, who lived in the same block with her husband Dr. E. Raphael Michael and their two daughters, “vocalized” with him, recalled her daughter Vernoca, now executive director of the Robeson House.

Her father, Vernoca added, was Robeson’s spiritual mentor.

Bell noted in her book that Robeson – who spoke or sang in at least 20 languages – sometimes read French and German newspapers to her and Marian, and translated the articles for them. He went out to the movies (he saw “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner”) or watched sports on television, according to Bell.

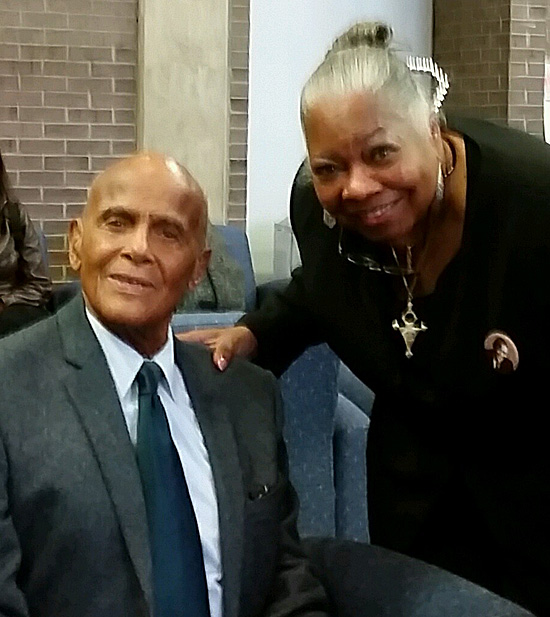

This was also a house where Robeson welcomed friends whom he had known for years, among them Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee, and Harry Belafonte. Charles L. Blockson, who amassed a collection of African American history that is now housed at Temple University in Philadelphia, arrived, too, having met Robeson for the first time after he moved in with Marian.

Robeson’s health started to fail and his body became frail. On good days, he came down the stairs of the house from his second-floor bedroom to sit on the porch or inside the house. Other days, he remained in bed. His bedroom still has its original furniture.

Arcenia McClendon was a young teacher in her 20s, and she lived with her mother just around the corner. She’d see Robeson and Marian on the porch, and would wave to them. One day, he was not there and Marian mentioned that he was not feeling well and was in bed.

Marian invited her in to see him. When she got to his bedroom, McClendon nervously listened as Marian told him that he had a visitor. Robeson was silent; then McClendon said she was from Laurel, MS.

“Leontyne Price,” Robeson said. Price, the famous soprano, was from Laurel, and Robeson had been one of her early benefactors.

This historic house – built in 1911 by architect E. Allen Wilson – sits among the people for whom Robeson agitated. He’d spent a large part of his life as a world-renowned and heralded singer and actor, but once he started speaking out about the injustices confronting African Americans and poor people all over the world, he was hounded by the U.S. government.

He was accused of having Communist leanings, and was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1956 where he refused to answer the question of whether or not he was a Communist. The State Department revoked his passport, and it was later reinstated through the courts. The government’s relentless campaign robbed him of his livelihood and his health.

The FBI kept an open file on Robeson even while he lived in Philadelphia as an elderly man who was no longer active.

After Robeson died in 1976 and Marian a year later, the house was left to Paulina. It had been vacant for more than 12 years when the West Philadelphia Cultural Alliance bought it in 1994. The alliance was formed in the 1984 to help satisfy the city’s need for more cultural institutions in its neighborhoods.

The alliance was looking for a place to carry out its mission, and the house where the famous Robeson once lived was ripe for a new purpose (squatters had already taken over it). The alliance bought the house and the attached twin, and sought the community’s advice on whether renovating it to be used for cultural events was the best use. The response was positive.

So the alliance under the direction of Frances P. Aulston, the driving force behind the house, went about restoring it as a legacy to Robeson, securing funding from a variety of sources. The restoration was mostly completed in 2015.

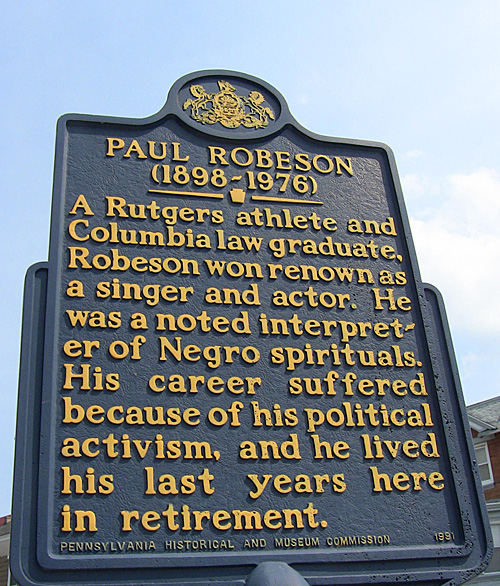

In 1991, the Paul Robeson House was declared a historical landmark by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. On the sidewalk in front of the house, a state historical marker was erected to tell the world of the historical significance of the house and Robeson himself.

In 2000, the house became an Official Project of Save America’s Treasures and is listed on the National Register for Historic Places. In 2005, it was listed on the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s 2004-2005 “Restore America” sites.

Today, the Paul Robeson House and Museum offers tours of an exhibit titled “Paul Robeson: Up Close and Personal” consisting of record albums, paintings, books, photos and other artifacts pertaining to the man. It also offers space for art shows, community meetings and other events.

Not far from the house, at 45th and Chestnut Streets, is an oversized mural of Robeson that faces a high school bearing his name.

The house is one of several centers devoted to his life, including the Paul Robeson Cultural Center at Rutgers University (where he was an All-American athlete), Paul Robeson Cultural Center at Pennsylvania State University and the Paul Robeson House of Princeton.