Paul Robeson was such an illustrious figure that he sometimes drowned out the people around him. One such person was his wife and manager Eslanda Cardozo Goode Robeson. “Essie,” as she was called, was a photographer, actress, world traveler, author and activist in her own right.

To make sure that she gets her due, the Paul Robeson House and Museum has organized an Eslanda Goode Robeson Research & Study Group. The group members are seeking others like themselves who believe that Eslanda, too, has a story worth telling.

“They say behind every good man there’s a woman,” said Denise Campbell, one of the organizers of the study group, “but it went much much beyond that. … She wasn’t behind him. She was in front of him.”

The idea for the study group grew out of a desire by Vernoca L. Michael, executive consultant at the house, to shine a light on the woman she calls “Aunt Essie.” The Michael and Robeson’s families were good friends.

Campbell became interested in the project during a house tour after Michael expressed her sentiments about highlighting Eslanda.

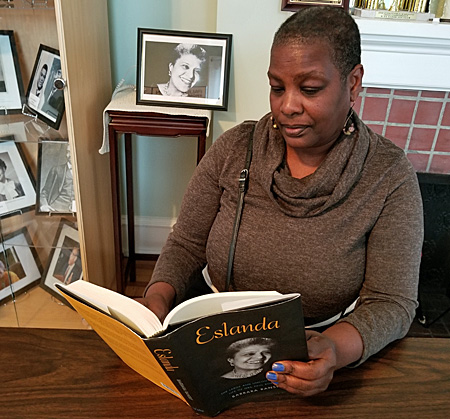

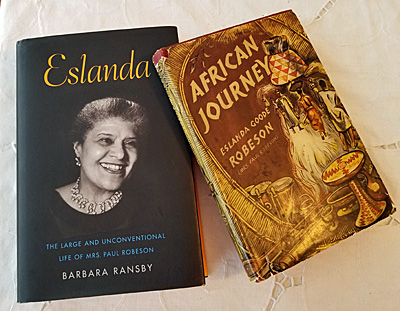

“Something just struck in me that that was something I would be interested in participating in,” Campbell said. “So I put this book (‘Eslanda: The Large and Unconventional Life of Mrs. Paul Robeson’) on hold at the library and when I got it and started reading it … I was fascinated from the first page.”

About Eslanda Robeson

Eslanda Cardozo Goode was much more than just the mate of Paul Robeson. She was an “anthropologist, a prolific journalist, a tireless advocate of women’s rights, an outspoken anti-colonial and antiracist activist, and an internationally sought-after speaker.”

She born in 1895 in Washington, DC, the daughter of a clerk in the War Department and granddaughter of a black elected official in South Carolina during Reconstruction. She graduated from Columbia University in New York with a degree in chemistry. She worked at New York-Presbyterian Hospital, becoming the first black person to head its surgical pathology department.

It was during her time at Columbia that she became an activist and met Paul Robeson. They were married a year later in 1921. She continued working at the hospital while managing his singing and acting career, but eventually quit the job to manage him full time.

In 1930, she wrote a book about Robeson’s life titled “Paul Robeson: Negro.”

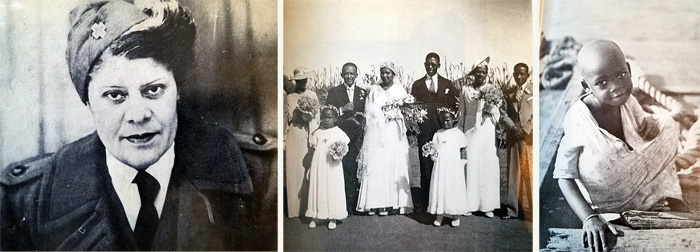

Eslanda was also an actress, appearing with her husband in the 1930 silent film “Borderline,” about a biracial love affair between a white man and black woman, whom she portrayed. She also performed in other independent films.

A year later, when the couple was living in London, she got an anthropology degree and looked to Africa for research and study. She made her first trip there in 1936 with her son Pauli, eventually writing a book “African Journey (1945),” based on her diary of the trip. She made two other trips, in 1946 and 1958.

She worked in support of African independence and rejected the notion of the continent being a place of primitive people. “When I travelled through AFRICA, I discovered that I belonged to the AFRICAN family, with 150 million AFRICAN RELATIONS, with an ancient and honorable historic and cultural background,” she said.

She wrote “American Argument,” a book about social and political issues, with author Pearl Buck as the editor in 1949.

When Robeson went to Russia in the 1930s, Eslanda accompanied him, and they both returned even more enlightened about the inhumanity of their own country. Both spoke out against racism, and over the next decades, lost the comfortable life they had lived. Their concerts dwindled, and many in the country turned their backs on them. Like her husband, she was called before the House Un-American Activities Committee in the 1950s to testify about whether or not she was a member of the Communist Party. Unfazed, she refused.

“All I ever feared were cats,” she is quoted as having once said.

The State Department revoked their passports, cutting off their income from foreign concerts at a time when Robeson was blacklisted at home. The passports were returned in a Supreme Court decision nearly five years later.

Eslanda was diagnosed with breast cancer in 1963 and died two years later. The next year, Robeson came to live with his sister Marian at the house that now bears his name.

Aim of the study group

Campbell says she would like the group to acknowledge Eslanda through activities at the house.

“I hope the study group will be in the forefront of developing different ways of having her story made public,” Campbell said. “That could be public presentations, that could be commemorations. Maybe we could plan something around her birthday (December 15) so that more and more people get to know who she is.”

____________________________________

If you’d like to join the study group or to find out about meeting times, email wphlca@gmail.com or call 215-747-4675.